Prefer to listen instead? Click here to listen to the audio version of this blog on Spotify.

If you’re longing to draw closer to Jesus this Holy Week—to slow down, to pray, and to really experience His Passion—we’d love to invite you into Holy Week with Mary, a 7-day devotional that walks day by day alongside Mary through Scripture, prayer, visio divina, and simple, meaningful action steps. It’s a way to walk the road to Calvary with the one who never looked away.

What Mary teaches us about walking through suffering with quiet strength.

Several years ago, a dear friend’s young son was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive form of blood cancer.

He was just nine years old—and already carrying the weight of a rare genetic condition called Sotos syndrome, which causes gigantism and developmental disabilities.

For three agonizing years, my friend paced the halls of the oncology ward, praying—pleading—that her son would survive.

She told me how the parents on that floor always knew when death had come. They could hear the wailing, the screaming, the women being supported down the hallways as they sobbed.

The sound of a heart shattering just beyond the curtain. And every time she heard it, she wondered if she might be next.

Her son nearly died more times than she could count. After one five-hour emergency surgery, a surgeon emerged, looked at her and her husband, and said, “You’re religious? You should pray.”

And she did. Over and over. Through chemo. Through infections. Through night watches and silent tears. Through months of waiting.

Every moment of those years was a wilderness of uncertainty—marked by waiting, aching, and begging God to move. I can’t even begin to imagine what it’s like to walk through that desert and wait and wait and wait for miracles to come.

Praise God, at the end of those three years, the cancer was gone. Her son survived. And now, almost ten years later, he is still alive.

Every time she shares about that experience, I think of Mary.

Mary did not have to question IF her son would die, she knew that sorrow was coming for her heart like a sword.

As Christians and humans, we understand that waiting and suffering will come in this life.

It may not take the form of a hospital room, but it comes through miscarriage, chronic pain, financial hardship, anxiety, infertility, betrayal, loneliness, and the ache of unanswered prayer (to name just a few).

Even if we’re not walking through acute suffering right now, we live in a world in exile—waiting for Christ to come again and make all things new. As Scripture reminds us: “In the world you will have trouble, but take courage, I have overcome the world.” (John 16:33)

We are guaranteed suffering and sorrow, times of desert dwelling and trials. And while it can feel disorienting or even senseless, Scripture reminds us that with God, none of it is wasted. From the beginning, God has been weaving a story of redemption through sorrow. And no one knew that more intimately than Mary.

What Mary Knew

To understand how Mary responded to suffering with such faith, we have to understand what she already knew—not just from the angel’s words, but from Scripture itself.

As a faithful Jewish woman, Mary would have been deeply familiar with the Old Testament Hebrew Scriptures—especially the Torah (Genesis through Deuteronomy), the Psalms, and the Prophets. The Jewish people lived, in all aspects of their lives and culture, in deep anticipation of the Messiah.

And scripture was central to that expectation. From a young age, Mary would’ve internalized the language, rhythm, and theology of God’s Word through prayer, song, and tradition.

Every year, she would’ve celebrated Passover and remembered the blood on the doorposts—the sign that spared Israel’s firstborn and led to their freedom. She would’ve fasted on the Day of Atonement, the solemn day when Israel begged God for mercy and the high priest entered the Holy of Holies to offer sacrifice for the people’s sins.

She would’ve lit candles for Hanukkah, remembering how God preserved His people and rededicated the Temple. She may have built tents for the Feast of Tabernacles, recalling the time Israel wandered in the desert and God dwelled with them.

She couldn’t have known that one day she would become the new dwelling place of God, that she would carry the true High Priest in her womb, offer Him, the true Passover Lamb, at the foot of the Cross, and watch as His blood—like the lamb’s—marked the doorposts of a new and everlasting covenant.

But she would’ve known the prophecies, prayed with her people for their Messiah. She would have known the Scriptures that foretold the Messiah’s coming, his death, and his victory. And we don’t have to guess at this. While we can’t say for sure whether she received formal education, the evidence of her fluency in Scripture is everywhere. Her Magnificat alone is a masterwork of biblical reflection—not a direct quote here and there, but a seamless, Spirit-filled song woven from the Psalms, the prophets, and the prayer of Hannah.

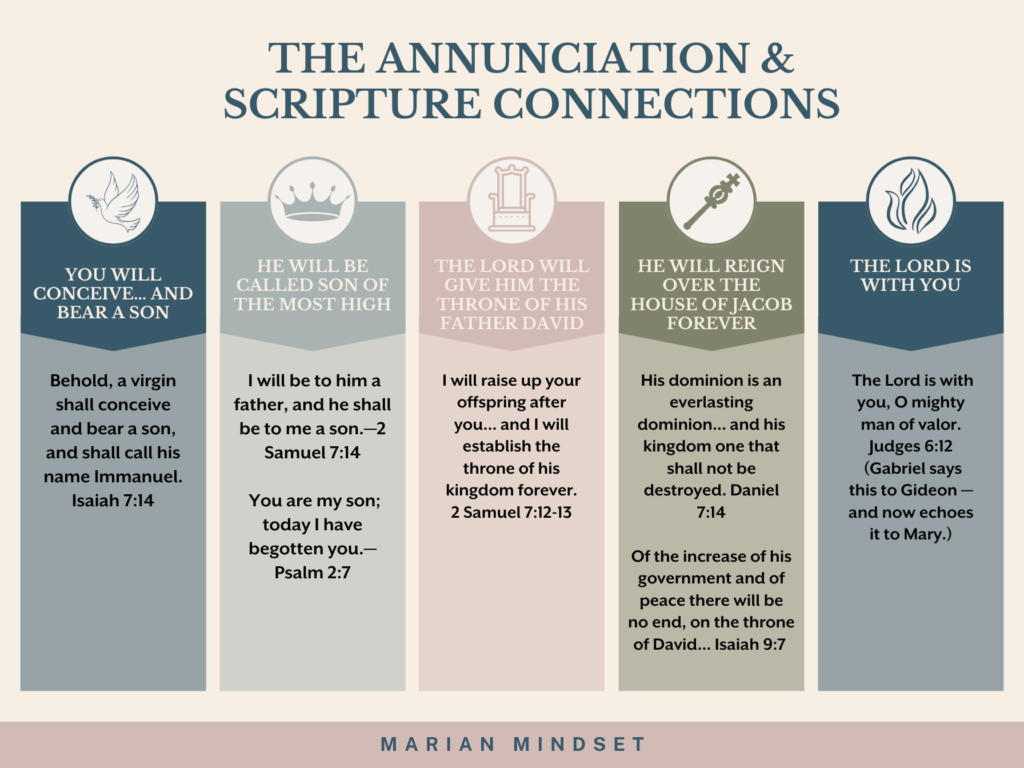

When Gabriel appeared to her, his words—while unexpected—would not have been foreign. He spoke to her through echoes of the scripture, passages she would’ve known well.

Let’s take a look:

When she gave her fiat, she was knowingly stepping into the tradition of the women come before her—from Eve, Sarah, Rebekah, Leah, Miriam, Hannah, Judith, Esther and so many more. The Catechism describes that moment as the “dawning of the fullness of time,” when Mary’s prayer cooperated uniquely with the Father’s plan of loving kindness (CCC 2617). Her yes was not a vague or naive surrender—it was a theologically rich, historically conscious act of faith, one that united her to her Son “unto the cross” (Lumen Gentium 58).

She understood that her fiat was the fulfillment of numerous prophecies, and that her sweet baby would be the long-awaited Messiah: the Seed who would crush the serpent, the Son of David whose kingdom would never end, the Lamb whose blood would mark the doorposts of redemption for all humankind.

But Mary’s ‘yes’ to that promise didn’t magically clear her path and make everything easy. Like the women of old, and like Israel itself, Mary was called into a kind of wilderness. A place of trust, surrender, and waiting. She shows us how to walk with God when the road is unclear, when the fulfillment is still unfolding, and when the cost is great.

Let’s look at just a few of the prophecies she would have known, how they shaped the way she walked through that wilderness with faith, and how we can do the same.

Prophecy #1: The Protoevangelium (Genesis 3:15)

“I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel.” Genesis 3:15

By the time we reach Genesis 3:15, a lot has already happened. Satan has come to Eve and planted the seed from which, as the Catechism says, “all subsequent sin” would grow—distrust in God’s goodness (CCC 397). Adam and Eve have sinned and hidden themselves from God as He walks through the garden in the evening breeze.

And yet, when it becomes clear what they’ve done, God doesn’t begin with punishment; He begins with a promise. This verse, known by the Church as the Protoevangelium (literally “the first good news”), is the first announcement of the Gospel in Scripture.

It is a prophetic declaration of hope, a promise that evil will not have the final word. A woman will come, and her offspring will crush the head of the serpent.

From the very beginning, God reveals His plan of salvation—a New Adam (Christ) and a New Eve (Mary) who will, together, overcome the sin that began in Eden. It’s an incredible display of mercy: before God speaks of exile or toil or sorrow, He promises redemption.

It also tells us a great deal about Mary. She isn’t named in this prophecy, but is referred to simply as “the woman.” That might seem generic—or even insignificant—until we realize it’s a very intentional choice. In salvation history, titles matter. Just as Jesus is called the Lamb of God or the Son of Man to reveal His mission, Mary is called Woman to reveal hers.

Scripture isn’t just recording a personal story, it’s unveiling a cosmic plan. The title Woman places Mary in direct contrast to Eve, the first woman, whose disobedience opened the door to sin. Mary’s obedience, by contrast, helps open the door to salvation. She is the Woman foretold in Genesis 3:15—the New Eve, who would stand in enmity with the serpent and bring forth the Redeemer.

Jesus confirms this identity when He uses the same title for her twice: once at the wedding at Cana (“Woman, what does this have to do with me?” – John 2:4), and again from the Cross (“Woman, behold your son.” – John 19:26). To modern ears, that might sound distant, even cold—but to Jewish and biblical ears, it was a profound signal. Jesus wasn’t distancing Himself from Mary. He was revealing her true identity. She is not just His mother — she is the Woman. The one who would walk with Him from the wedding feast to the foot of the Cross, sharing in His mission to redeem the world.

And as a faithful daughter of Israel, Mary would have known this prophecy well. Genesis 3:15 is and was the foundational promise of hope spoken into humanity’s darkest moment. It was the verse that ignited Israel’s long wait for the Messiah, the one who would crush the serpent’s head and restore what had been lost.

Mary may not have understood the full extent of her role from the very beginning, but when the angel Gabriel greeted her with words that echoed prophecy and announced that her child would reign on David’s throne forever, she would have recognized the weight of it. Because she also would have known the next prophecy well: that of the Suffering Servant.

Prophecy #2: The Suffering Servant (Isaiah 53)

“He was despised and rejected by men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief; and as one from whom men hide their faces he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows…But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his wounds we are healed.” — Isaiah 53:3–5

Isaiah 53 is actually part of a larger section often called the “Servant Songs” (Isaiah 42, 49, 50, and 52:13–53:12), written by the prophet Isaiah in the 8th century BC. These songs describe a mysterious “Servant of the Lord” who is chosen by God to bring justice, restore Israel, and ultimately suffer and die for the sins of others.

Most scholars agree that this particular song, Servant Song Four, begins in the previous chapter (52:13), which opens with: “Behold, my servant shall prosper; he shall be exalted and lifted up, and shall be very high…”

But this incredible exaltation is followed by humiliation, suffering, and rejection—a reversal that would have surprised many in Israel who were expecting a triumphant, political Messiah. Because the people Isaiah was writing to were a people either already in, or heading toward, exile and destruction. They were hoping for and expecting the savior to sweep in with armies and power, decimating their enemies and leading them as a people triumphant.

But God, in His infinite mercy, chose not to bring judgment as they expected. Though Israel had repeatedly broken the covenant, He revealed through Isaiah that salvation would come—not through force or conquest—but through a servant who would willingly suffer for others.

In the ancient Jewish world, suffering was usually seen as a result of sin—something a person brought upon themselves through disobedience. But Isaiah 53 flips that expectation. The Suffering Servant doesn’t suffer for His own sins; He suffers for others. This was a revolutionary idea in Isaiah’s time.

The Jewish people annually performed a ritual that did something similar: the Day of Atonement, described in Leviticus 16. On this most solemn day of the year—Yom Kippur—the high priest would enter the Holy of Holies, offering blood sacrifices to atone for the sins of the people. But there was a second part of the ritual that’s even more striking in light of Isaiah’s prophecy: the scapegoat.

Two goats were chosen. One was sacrificed, its blood sprinkled on the altar. The other was kept alive. The high priest would lay his hands on this second goat, confessing over it all the sins of Israel, and then it would be driven into the wilderness, symbolically carrying away the sins of the people. (Leviticus 16:21–22)

Isaiah 53 echoes this with remarkable clarity:

“The Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all” (Isaiah 53:6).

“Like a lamb that is led to the slaughter…” (Isaiah 53:7).

Unlike in the ritual, the Suffering Servant is both lamb and scapegoat—the one who dies and the one who carries sin away.

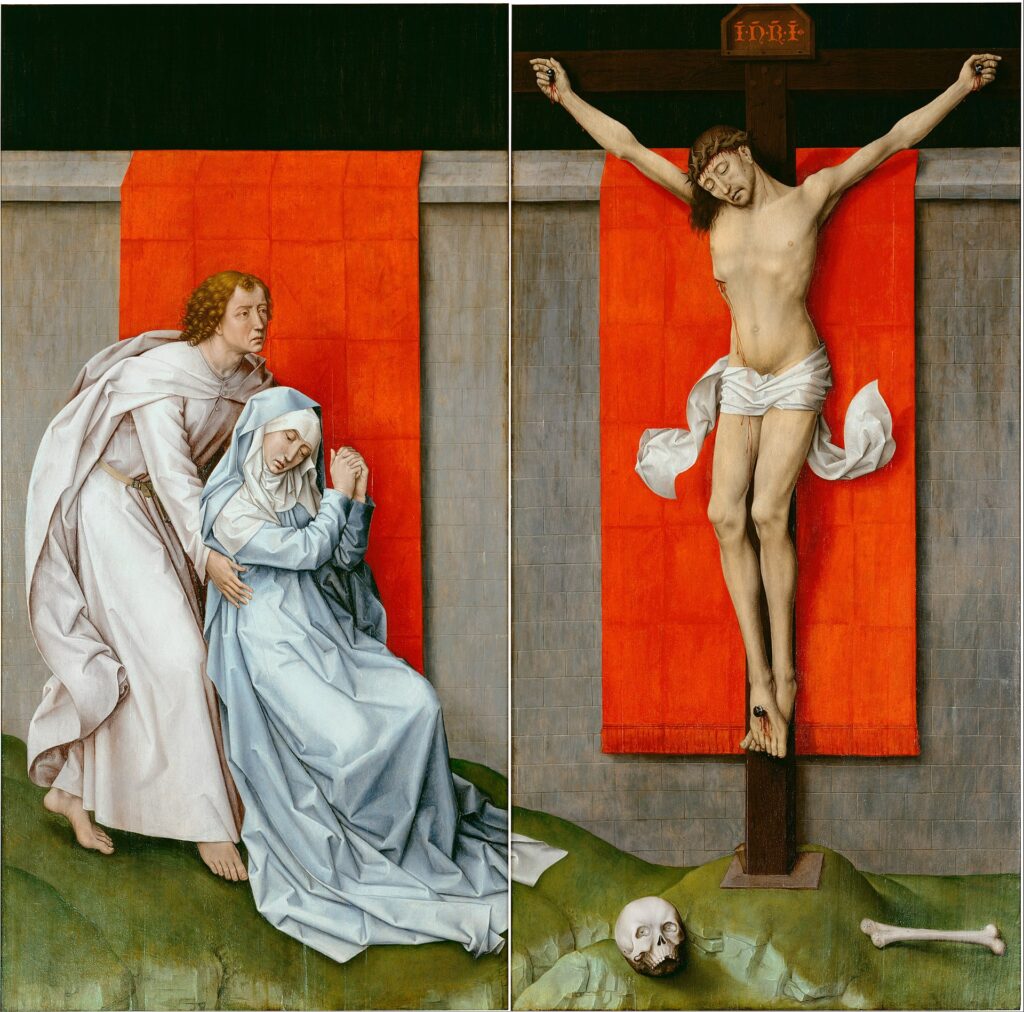

When we view Mary standing beneath the Cross, we can begin to understand the weight of this imagery. She knew the rituals. She knew the prophecies. And she knew that her Son was not only the High Priest offering the sacrifice—He was the sacrifice. And not just for Israel, but for the whole world.

It’s no wonder Isaiah 53 is read every Good Friday—it describes Christ’s Passion in heartbreaking detail centuries before it occurred. And when read with Mary in view, it becomes even more poignant.

As she watched Him suffer, Mary didn’t simply witness the fulfillment of Isaiah’s Suffering Servant—she entered into it. The sword Simeon foretold wasn’t just metaphorical; it pierced her heart as surely as the spear pierced His side. As St. Bernard of Clairvaux writes, “Only by passing through your heart could the sword enter the flesh of your Son… She died in spirit through a love unlike any other since His.”

Mary did not share in Christ’s physical Passion, but she endured a spiritual passion, a martyrdom of the heart. She stood beside the true Suffering Servant not only as a grieving mother, but as a co-sufferer (what some Church theologians and saints have called a “Co-Redemptrix”), whose love refused to look away.

Prophecy #3: The Sword of Simeon (Luke 2:25-35)

“Now there was a man in Jerusalem called Simeon, who was righteous and devout. He was waiting for the consolation of Israel, and the Holy Spirit was on him. It had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he would not die before he had seen the Lord’s Messiah. Moved by the Spirit, he went into the temple courts. When the parents brought in the child Jesus to do for him what the custom of the Law required, Simeon took him in his arms and praised God, saying: “Sovereign Lord, as you have promised, you may now dismiss your servant in peace. For my eyes have seen your salvation, which you have prepared in the sight of all nations: a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and the glory of your people Israel.” The child’s father and mother marveled at what was said about him. Then Simeon blessed them and said to Mary, his mother: “This child is destined to cause the falling and rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be spoken against, so that the thoughts of many hearts will be revealed. And a sword will pierce your own soul too.” — Luke 2:25-35

When Mary and Joseph brought Jesus to the temple to present Him to the Lord, they were doing what faithful Jewish parents had always done: following the law. They were there for Mary’s purification, to offer a sacrifice, and to dedicate their firstborn son to God. But what unfolded in the temple that day went far beyond ritual.

An old man named Simeon, full of the Holy Spirit, approached them and took the child in his arms. He burst into a canticle (a common occurrence for those meeting the Messiah—first Mary, then Elizabeth, and now Simeon!), praising God and declaring that this baby was the long-awaited Messiah—the light for the nations and the glory of Israel. And then he turned to Mary and said something she would carry for the rest of her life:

“Behold, this child is destined for the fall and rise of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be contradicted—and you yourself a sword will pierce.” (Luke 2:34–35)

We may read that line as just a poetic foreshadowing of Calvary. But Simeon’s words are part of something much bigger. They’re woven into the whole story of that day, the presentation, the offering, the temple, the law, the waiting, and the hope. With his words, Simeon isn’t just describing a mother witnessing the suffering of her child—he’s revealing Mary’s unique role in the mission of Jesus from the very beginning. The “sword” that will pierce her heart isn’t just a poetic image. It’s a sign of how profoundly her life is bound to His.

What happens in the temple that day isn’t a sentimental blessing. It’s a prophetic moment, rich with meaning. Jesus is being offered. Sacrificed. Ransomed. The words used in this scene—presentation, purification, redemption, offering—all point to a future that involves suffering. And Mary, standing beside her Son, is part of that offering.

As Pope Benedict XVI once said in his Homily for the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord and the Day of Consecrated Life, February 2, 2006:

“She, too, in her immaculate soul, must be pierced by the sword of sorrow, thus showing how her role in the history of salvation is not finished with the mystery of the Incarnation, but is consummated in the loving and sorrowful sharing in the death and Resurrection of her Son. Carrying her Son to Jerusalem, the Virgin Mother offers him to God as the true Lamb who takes away the sins of the world; she hands him to Simeon and Anna as an annunciation of redemption; she presents him to all as light for a secure journey on the path of truth and love.”

Mary doesn’t just carry Christ into the temple—she offers Him, knowing that He is the Lamb of sacrifice. And in doing so, she begins the journey of participating in His redemptive work, not just as His mother, but as His first and most faithful disciple.

Simeon speaks directly to her, not to Joseph, and says, “You yourself, a sword will pierce.” The wording is intimate and emphatic—your own soul. Her suffering won’t be a vague sorrow shared by all mothers. It will be personal, piercing, and inseparable from her Son’s rejection and crucifixion. Every moment Jesus is misunderstood, opposed, or hated—her heart will be pierced, too.

And the sword is not just for Calvary. It’s for every step of His mission. Mary is a woman who walks with the sword poised above her heart, a constant companion—from Bethlehem to Egypt, from the temple to the foot of the Cross. Her suffering, as Simeon reveals, is not accidental or secondary. It’s part of the mystery of salvation.

Through that sword, Mary is united to her Son’s redemptive work. Her pain reveals something essential: that to love the Messiah means to suffer with Him. And this suffering—hers and His—is what will reveal the hearts of many. Simeon’s prophecy is the first glimpse of the Cross. And Mary, even in this quiet moment at the temple, is already beginning to carry it.

A Mother for the Wilderness

So much is said of Mary in scripture. There are prophecies and canticles and all other manner of spoken words over her life. But Mary’s response is something completely different. She remains mostly silent throughout all the Gospels.

The words are spoken about her, and even to her, but she receives them without protest, without explanation. Her response isn’t verbal—it’s interior. She listens. She ponders. She carries the weight of it all in her heart.

This silence is not absence. It is constancy. It is the stillness of one who trusts, even in mystery. As Cardinal Robert Sarah writes in The Power of Silence: Against the Dictatorship of Noise:

“In the Gospels of Mark and Matthew, there is no mention of Mary’s words. In God’s plan, the Virgin is inseparably bound up with the Word. The Word is God, and the Word is silent. She is completely under the influence of the Holy Spirit, who does not speak. The attitude of Mary is that of listening. She is completely turned to the word of the Son… Mary’s fiat is a silence to which the Mother of Christ will remain faithful for eternity. Noiselessly, Mary offers her life and that of her Son to the Eternal Father. Noiselessly, she says fiat in advance to the death of Jesus. As a mother, she sees the terrible agony of Jesus, whose body is covered with wounds and bruises. She stands, clinging to the Cross, and the blood of her Son flows down on her face and arms. Imitating Jesus, Mary can say: ‘No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord’ (Jn 10:18). The Virgin is crucified and dies mystically with her Son.”

In her stillness, in her silence, Mary shows us how to carry sorrow in the wilderness: not with loud protest or certainty, but with deep interior consent. With her eyes fixed on God, she walks the road of suffering with grace, reminding us that even in the silence, even in the waiting, we are never alone.

As we enter into Holy Week, we will see firsthand the fruition of all those ancient prophecies. The Lamb will be led to the slaughter. The serpent’s head will be crushed. The sign of contradiction will be lifted high. And beneath it all, a mother will remain—silent, steadfast, and pierced.

Thinking on this, my mind is drawn once again to that ghastly place, the children’s oncology ward. I cannot begin to imagine what it does to the heart to watch your child die. To hold them in your arms as they breathe their last. To cradle them after the monitors have been removed. To watch them covered in a sheet and wheeled out of a room.

What does that do to a mother’s heart?

Again then, I think of Mary. As she stood there on Calvary, looking up at her only Son.

When He cried out from the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?,” did she remember teaching Him that psalm in the garden while they planted?

What did she think and feel as they took down her Son’s body?

Did she cradle His head as she did the night He was born? Those same loving arms now trying to hold together a broken body, naked and beaten?

Did her fingers tremble when she removed His crown of thorns and ran them through His matted, bloody hair? Did she have a curl set away in her bedroom in Nazareth, clipped when He was a boy?

Did she smooth the brow she once kissed, when He lay heavy on her chest, sweat-damp from play and dreams?

Did she kiss the laugh lines on His face?

Did she wipe the blood from His lips, remembering when He was a few weeks old and so desperate to nurse He tried suckling her cheek? Or when He was a grown man, when He’d bend to kiss the top of her head?

Did she weep over His nail-pierced hands, remembering the times those hands presented her with flowers and shells and worms, the treasures of a child’s heart and Her son’s own creation?

Did her heart break open at the weight of Him in her arms again, not the soft, squirming weight of a baby, or of a tired boy all played out, but the heavy, terrible stillness of death?

Did she think of Eve, who, in that moment, Jesus was surely on His way to redeem?

Did she think of all the fathers whose stories she grew up learning—Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, Solomon? Did she feel the presence of all salvation history pressing in around her, the culmination of every covenant, every prophecy, every aching hope?

What happened to her mother’s heart she when looked down at the God who once kicked in her womb and now lay breathless in her lap?

Mary knew the road ahead would break her heart.

She had heard the prophecies. She had sung the Psalms. She had carried the Word of God within her body and pondered it within her soul. She had given her yes not just once, but over and over—each time the sword pressed closer to her heart.

And still, she stayed.

She teaches us that we don’t need all the answers to trust God. That faith doesn’t always look like clarity. Sometimes it looks like staying in the room, holding the weight of what you cannot fix, and whispering yes to God again.

As Holy Week unfolds before us—the Passion, the Cross, the silence of Holy Saturday—may we walk it like Mary: attentive, steady, pierced, and faithful. And when we find ourselves in the wilderness of our own lives—when the prayers go unanswered, when the suffering feels senseless, when the miracle hasn’t come—may we remember the woman who stayed.

The woman who wept.

The woman who believed.

The woman who teaches us how to hope in the dark.

Mother of unrelenting sorrow. Mother of agony unleashed. Mother who said yes to the sword and the grave so we might be free.

Pray for us.

Want to walk with Mary through Holy Week?

This Holy Week, if you’re longing for a way to stay close to Mary—to pause, reflect, and pray through the sorrow—we’d love to invite you to Holy Week with Mary.

This simple, 7-day devotional offers daily guidance through scripture, prayer, visio divina, and daily action steps to help you enter into the mystery of Christ’s Passion through her eyes—and walk the road to Calvary with a mother who never looked away.

Read the rest of the Lenten series:

Into the Wilderness: A Lenten Pilgrimage with the Desert Fathers and Mary (Part One)

Into the Wilderness (Part Two): St Anthony and the Desert Within

Into the Wilderness (Part Three): Abba Isaac and Prayer as Daily Bread

Into the Wilderness (Part Four): Evagrius Ponticus and Guarding Your Mind

Into the Wilderness (Part Five): St John Cassian and the Power of Fasting

Into the Wilderness (Part Six): Abba Moses and Perseverance in the Wilderness

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment